Throughout Chinese history, many emperors loved calligraphy so much they became highly accomplished in the field. An old Chinese adage holds, "Calligraphy is a mirror to a person's character." The calligraphy of emperors reflects the different characters that ruled the nation, and even their leadership abilities.

When speaking of emperor calligraphers, Zhao Ji (1082-1135) or Emperor Huizong of the Song Dynasty (960-1279), immediately springs to mind. His writing style, comprising thin and straight strokes, is called "slender gold" style. His horizontal strokes ended with hooks, the vertical strokes with points. His slanting strokes were sharp as knives, and the vertical hooks as slim and tall as a fine young man. His style reflected a pursuit of perfection while obeying regulations. On the other hand, his endless pursuit of beauty in form made him overlook the overall setting, indicating that he was deficient in resolution, persistence and creativity. His writing style reflected his rule. During his 25 years of governing, Zhao Ji was so addicted to calligraphy and art that he devoted little time to knotty political issues. He first made Cuju (a prototype of football) star Gao Qiu his chief military commander, and then handed almost all governance to a few treacherous court officials, while he devoted himself to art and culture.

Not surprisingly, calligraphers and painters enjoyed their highest social elevation during Zhao Ji's reign. A vast collection of classical calligraphic and painted works was created, and the era produced more masters than any other. As well as calligraphy, Zhao Ji was good at writing poetry and lyrics, composing music, and dancing. Known as a master of the arts, he also spent much time collecting cultural relics, especially calligraphic works and paintings. The imperial art academy was expanded during his reign, and all ancient calligraphies and paintings preserved in the palace collection were catalogued in books that survive to this day. In this respect, he made great contributions to the development of the Song Dynasty's imperial art academy and court style painting, as well as to the sifting and preservation of ancient art works.

However, the emperor's focus on beauty brought him a miserable death. His empire faced many outside threats, and high achievements in the artistic realm could not protect him from invasion by northern nomads. He was captured in 1127 after his capital fell, and ended his life as a captive in Wuguo Cheng (now known as Yilan in Heilongjiang Province).

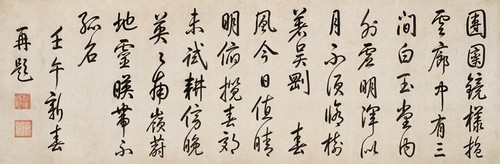

Another master calligrapher is Emperor Qianlong (1700-1799) of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), though he was quite different to Zhao Ji. Qianlong loved calligraphy all his life. He collected famous works, read them and inscribed comments. Nowadays almost all extant authentic ancient works carry his seal. Qianlong's handwriting was stretched out, bold, but formulated in accordance with regulations. His characters were fluid in their strokes, and balanced in construction. Their boldness and vigor came from the emperor's personal characteristics, but were also related to the time he lived in. After ascending the throne, Qianlong defended his empire from invasions and encouraged land reclamations. He banned all books that went against his government and put the authors in jail, thus consolidating his reign. Referring to culture, he set up a publishing house to compile history books. His pride at what he perceived as enhanced national strength was evident in his calligraphic works.